Supplemental Episode 016: Learning to Delegate

Meet two statesmen who really mastered the art of saying, “That’s not in my job description.”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: More Options

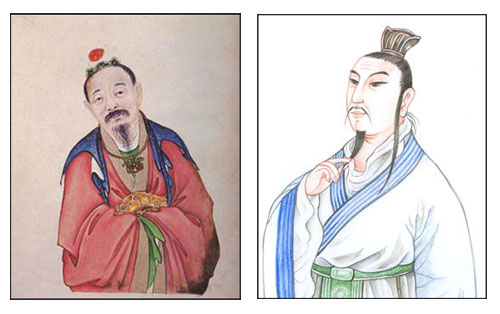

Bing Ji (left) and Chen Ping

Transcript

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is a supplemental episode.

In this episode, we’re going to look at a story related to Bing (3) Ji (2) and Chen (2) Ping (2), two famous officials from the Western Han dynasty. One of Zhuge Liang’s aides name-dropped them both as he tried to convince Zhuge Liang to delegate some of his responsibilities for the sake of his own health. The aide said, “Look at Bing Ji, who cared not for dying men on the road but worried about a panting ox, or Chen Ping, who did not know how much grain or money the state had.”

Now, on the surface, it would seem like those are not exactly good traits for a prime minister, but there are stories behind those references. Let’s first look at the story of Bing Ji. He was born sometime in the second century BC and died in 55 BC. There’s an interesting backstory about him that I want to a little bit about first before we get to the crux of our episode.

He started out as a provincial jailer and eventually rose to one of the highest officials in the judiciary in the capital, but then he was demoted back to the provinces for some transgression. Now, this was during the time of the Han emperor Wu (3), who lived to age of 69 and reigned for 54 years. That 54-year reign, by the way, would stand as the longest in Chinese history for 1,800 years. This emperor Wu was a very important ruler and oversaw China’s greatest expansion. But toward the end of his reign, he ran into some major turmoil.

In the year 92 BC, the wife of his prime minister was exposed for casting curses on the emperor, which led to the prime minister and his entire family being executed. But it didn’t stop there. Members of the imperial house were dragged into this mess, and somewhere along the way, an official who had a grudge against Emperor Wu’s heir apparent accused said heir apparent of partaking in witchcraft. Whether or not that was true soon became immaterial. The prince, feeling cornered, decided that fortune favored the bold. While Emperor Wu was out of the capital, the prince faked an imperial decree and launched an armed uprising in the capital. He killed the officials who were making accusations against him, but that was as far as fortune carried him. When the emperor heard that his son was leading an uprising in the capital, that pretty much confirmed everything he suspected, so he sent an army to put down this rebellion. The prince was defeated and committed suicide. But he wasn’t the only member of the clan to go down. His wife, his son, and his son’s wife were all executed. And even the prince’s grandson, an infant of just a few months, was arrested and put in jail.

And the guy who was in charge of the jail at the time? That’s right. None other than Bing Ji. He had been summoned back to the capital to help out with the caseload during all these purges. Bing Ji knew that the prince was innocent, so he looked after the dead man’s infant grandson in jail. He selected a couple female prisoners to nurse the baby, commuting their sentences for the duration.

Meanwhile, Emperor Wu’s paranoia continued to rage. Even after purging his own heir apparent and his family, the old emperor was still worried about potential challengers to his power. He got the notion that there was still an imperial aura hanging around the jail in the capital, so he sent a decree ordering that every prisoner in that jail, regardless of their crime, was to be executed. You know, why take any chances, right? Well, Bing Ji had a hunch that the old emperor might change his mind, so when the envoy arrived at the jail that night, Bing Ji shut the doors and refused to see him. Hey, you can’t disobey an imperial edict if the messenger can’t track you down to read the edict to you. And sure enough, by morning, the emperor had regretted his decision and rescinded that order. So Bing Ji saved the life of the infant.

Eventually, the infant grew into a child in jail. It wasn’t until age 5 that the kid was allowed to go and live with relatives on his late mother’s side of the family. Then, through many twists and turns, too many to go into detail here, this kid ended up being emperor, in part based on a recommendation by Bing Ji.

Now, you would figure that this was when Bing Ji cashed in on all that he had done for the new emperor. But he didn’t mention a word of how he saved the new emperor’s life when the emperor was just an infant. Eventually though, the truth came out, and the emperor was very touched and rewarded Bing Ji handsomely, eventually promoting him to prime minister.

All of that brings us to the point of our supplemental episode. So one day, prime minister Bing Ji went out on one of his frequent inspection tours outside the capital to see how the commoners were doing. On his way, he first came across a group of people who were brawling. These guys were really wailing on each other, and there were dead and wounded men lying along the roadside. But Bing Ji didn’t even try to stop the melee and instead just kept on moving.

Later on the same tour, Bing Ji and his entourage came across a farmer walking with an ox. As they passed, Bing Ji noticed that the ox was panting, and he immediately told his men to stop as he went and inquired as to how far that ox had walked and whether it was in good health.

One of the attendants in his entourage couldn’t help but ask Bing Ji why he cared so much about an ox when earlier he showed no concern at all about a brawl where human beings were being bludgeoned to death. Was he placing the life of cattle over that of people?

To this, Bing Ji answered, “There are government officials whose job it is to deal with brawlers, and it is sufficient for me to inspect the work of those officials periodically and reward or punish them accordingly. The prime minister is a high-level official, and he should concern himself with the important affairs of the state rather than a mere brawl.”

Ok, we’ll buy that, putting aside the idea that you could have, you know, maybe saved a few lives by stopping the brawl then and there. But anyway, let’s say you’re right and breaking up brawls is beneath the prime minister. But then why was the prime minister so worried about an ox?

To this, Bing Ji answered, “The weather shouldn’t be too hot right now, but if it’s hot enough to make an ox pant, it could be a sign that we are in for some abnormal climate, which could affect the harvest. That is why I inquired about the ox.”

Now, I can hear you saying, the brawl could have been an indication of potentially deep-rooted socialeconomic issues that could tear the empire apart, so shouldn’t the prime minister be worried about that, too? And you know what? You’re probably right, but that’s the way the story goes, so let’s just roll with it.

Now, on to the other guy, Chen Ping. He lived a good century and a half before Bing Ji and was an important adviser for the Supreme Ancestor, Liu Bang, in founding the Western Han Dynasty. He actually started out in the employ of Liu Bang’s chief rival, the warlord Xiang (4) Yu (3), but ran afoul of one of Xiang Yu’s top officials and so Chen Ping ran off and joined up with Liu Bang instead. His strategies played a key role in Liu Bang’s success in winning the empire, and Chen Ping then went on to play a key role in the administration of Liu Bang and a couple of his successors.

During the reign of the third emperor of the Han Dynasty, Chen Ping was appointed to Prime Minister of the Left, while an official named Zhou (1) Bo (2) served as Prime Minister of the Right, sharing the responsibilities. One day, the emperor summoned the two prime ministers and asked Zhou Bo if he knew how many court cases the government tried each year. Zhou Bo didn’t know the answer. The emperor then asked him if he knew how much money and grain the national treasury took in each year. Again, Zhou Bo didn’t know the answer and he was now so nervous that he was sweating like a pig.

But Chen Ping chimed in and said, “The answers lie with the people in charge of those areas. For the number of cases, your majesty should ask the minister of justice. For the amount of money and grain, you should ask the accountant of revenue.”

The emperor was like, well, that’s fine, but then what the heck do I need a prime minister for, much less two?

To that, Chen Ping, said, “A prime minister’s role is to assist the emperor by pacifying all those outside the empire, maintaining peace within the empire, and ensuring that all officeholders perform their duties properly.”

That answer not only appeased the emperor, but it made Chen Ping’s counterpart, Zhou Bo, incredibly ashamed, both for not knowing what the proper role of a prime minister was and for his own inadequate abilities in comparison to Chen Ping’s. So Zhou Bo soon stepped down to … umm … spend more time with him family, leaving Chen Ping in sole possession of the prime ministership.

So, the point of both of these stories is that people should understand their roles and not worry too much about things that are beneath their level of responsibilities. This was the message Zhuge Liang’s aide was trying to convey, but alas, Zhuge Liang just wasn’t much of a delegator. He just had to micromanage everything, and it contributed to his early demise. Let that be a lesson to all of us. Working ourselves to death overseeing every little detail may earn us outsized propaganda in a classic novel that endures for centuries, but it will NOT win us an empire.

And that does it for this episode. I’ll see you next time on the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. Thanks for listening!